Hip Hop Feminism

An analysis of hip-hop and female empowerment through the academic lens thanks to Professor Jiles

In her book Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America, the author Tricia Rose describes hip hop feminism as an opposition to blackness as a ‘tangle of pathology’ (e.g. propensity for poverty, sexual deviance, youth delinquency, crime) and to the undermining of Black cultural expression (Black culture as a threat or as a culture lacking in value). But what is hip-hop feminism, and how can it be applied to better understand the persisting misogynistic, double standard in the industry?

Hip-hop and rap continue to evolve, but the juxtaposition of how artists express their authenticity spans a long and arduous road (in the public eye no less), often navigating terrain that leans heavily into capitalism, racism, sexism, and predominant ideologies that female artists are not as valuable as men. This is evidenced in how, “controlling images of Black women function to reify dominant power relations of race, class and gender… (Hip-Hop Revolution, Ogbar, 16)”.

From female artists such as Nina Simone who boldly sang about everything—including sex—to today’s artists like Doja Cat, the commodification of Black women in society is continually met with disdain, exploitation, and in contrast, self-empowerment. The reclaiming of the Black image and how it is represented in media and institutions started by the 1960s, on through the 1970s when urban black and Latino youth created a new culture that sought to prove authenticity was not accurately represented, especially not through the white lens. “The centrality of African American art to hip-hop helps contextualize the aesthetic symbols and creative expression found in the early hip-hop community and how they were inextricably tied to the era of the 1970s, which saw the minstrel as anathema.” (Ogbar, pp.13)

Today hip-hop and rap artists have become influencers, cultural representatives, and industry leaders. However, female artists have had to fight through racial tropes, misogyny, objectification, and sexism for far too long. In order to fully understand the inextricably linked foundation of messaging that has categorically denied women in hip-hop a sense of power, it’s important to look at musical artists today and how they are actively rising above the bullshit.

Doja Cat is among those whose career has had a flurry of ups and downs, but her most recent album is an answer back to criticisms about her realness. When Doja first came on the scene with a song simply titled, “Moo”, she appeared in her video wearing a cow onesie, singing with French fries up her nose.

The song and video went viral for its catchy hook and absurdly comical visuals. The song, albeit silly, was what put her on the radar. In 2023, Doja Cat released an album that would be her new calling card and Scarlet is possibly the most authentic album she has ever released.

Authenticity is one of the main themes of Ogbar’s book, Hip-Hop Revolution. Hip-hop and rap have been the face of Black culture and urban life since it came on the scene, though the issues of authenticity have persistently been questioned. Are all rap artists thugs? Are they all womanizers or hoochies? Are they violent criminals? “The transitory popular images of blackness during the late 1960s and early 1970s shaped the ways in which black youth of the era viewed the mutability of the black image in popular culture as no other generation had. Still, many of the blaxploitation films did fixate, however, on characters who were in many ways a new expression of a pathological other: sexually lascivious, criminally inclined, violent, and impulsive.” (Ogden, pp. 17) Popular culture today is still placing these tropes onto rap artists.

Doja Cat references perception in her song, Attention. After mitigating haters via social media, Doja takes to TikTok to be her most authentic self, countering the image the industry placated. The album, Scarlet, is a very strong statement of self-empowerment and defying the public and industry perspectives on female rappers. The song, Attention, dissects standards of beauty, double standards in terms of sexism in rap, and it’s her anthem of not giving a f**k about what anyone thinks. Ogbar writes, “The desire to affirm authenticity and skill is ubiquitous artistic quality in the ‘rap game’. The criteria for authenticity, however, are dynamic.” In particular, Doja Cat takes control of her own authenticity and dismisses the misogynistic influence as evidenced in the lyrics:

Look at me, look at me, you lookin’?

My taste good, but I just had to redirect my cookin’

I coulda been an opener, I redirect the bookin’

I read it, all the comments sayin’, “D, I’m really shooketh”

“D, you need to see a therapist, is you lookin’?”

Yes, the one I got, they really are the best

Now I feel like I can see you bitches is depressed

I am not afraid to finally say shit with my chest

Lost a lil’ weight, but I ain’t never lost a tushy

Lookin’ good, but now my bald head match my-

Lookin’ good, but now they all sayin’ that I’m ugly

Boo-hoo, my ni**a, I ain’t sad you won’t fuck me

I’m sad that you really thought your ass was above me

This is her blatant rebuttal to anyone in the rap game or industry; especially those with “puppet strings” affixed to her. When you watch the video, this sentiment is seen throughout each scene as she walks through the streets, shoulder bumping strangers coming at her, and a very quick scene with her nude, but painted in devil and anatomy red. This visual provides a sense of power and independence from the prying eyes and opinions of those who lack their own originality and unique voice.

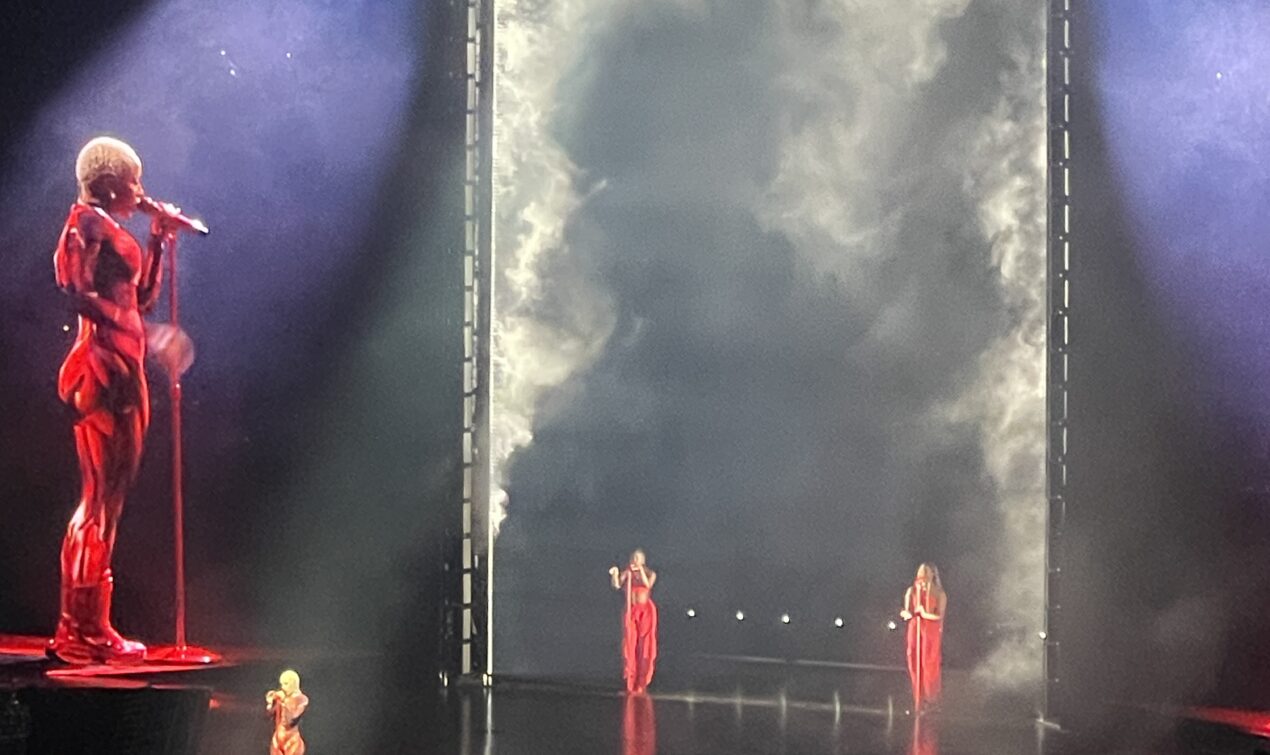

Last year when she toured, she performed wearing a suit that was a body suit, full of muscle and organs and it was her show of vulnerability. Similarly, the lyrics in “Attention” propagate this messaging:

The wage gap for many women of color is not only wider than the overall gender wage gap, but it is also closing more slowly.

AAUW Research & Data

Look at me, look at me, I’m naked

Vulnerability earned me a lot of bacon

I put a thong all in my ass and taught you how to shake it

I paid all my respect to those who taught me how to make it

And now I reap the benefits with no confrontation

Y’all fall into beef but that’s another conversation

I’m sorry, but we all find it really entertaining

‘Cause we all wanna see them slip and fall right on their faces

And we all wanna be the one to see the devastation

Not be in it, but ain’t the bad press good?

The disrespect’s real, how this Patek look?

Pull out the checkbook, now why your neck crooked?

I never learn to superstar from a textbook

Talkin’ ’bout, “She fallin’ off, why she get booked?”

Man, I been humble, I’m tired of all the deprecation

Doja Cat represents the pushback of how women “should be” perceived. She, unlike other rap artists, performs with an abandon that gives her freedom to challenge the status quo. She doesn’t represent thug life, and when she is painted as a “thug”, her response is not only categorically profound, it is exemplary of women asserting their dominance in a male-dominated industry. “Attention” is a warcry of sorts that questions the morality of the industry, the influence of women, and the objectification of rap artists steeped in stereotypes and racial tropes. The video was produced by Tetyana Robertivna Muinyo, better known as Tanu Muino — Ukrainian music video director, designer, stylist, photographer and film director. Muinyo’s work with artists Harry Styles, Monatik, Time and Glass, NK, IOWA, Cardi B, and Normani has earned her a place as a coveted producer willing to honor the vision of the artist, while not playing into the hands of traditional rap ideologies. The Doja Cat video for “Attention” is really a feminist message of self-evolution in the face of mounting feminine criticisms and political attempts to strip women of existing rights. The song is a mantra with a message that states Doja is no longer allowing industry heads and fans to dictate the worth and value of who and what she is and does. It’s a powerful anthem of sexual identity, hip-hop feminism and artistic prowess.

To paraphrase King, “Hip hop feminism can be seen as a direction that is independent of second and third wave feminism”, as proposed by Black Studies scholar Kimberley Springer and German hip hop feminist and rapper Reyhan Şahin. Şahin further defines hip hop feminism as a “theoretical and practical enactment of intersectional, sex positive and inclusive feminist ideas and concepts that draw on critical analysis of gender roles within hip hop culture” (2019: 111).

In other words, never underestimate the power of a woman with a voice … and a captive audience.

SOURCES

Doja Cat (2023). Scarlet Album, YouTube, “Attention” music video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agXQQDasq0U

Los40 (2022). Tanu Muino: the Music Director behind many of our Favorite Artists. https://los40.us/2023/tanu-muino-the-music-director-behind-many-of-our-favorite-artists-6163.html

Global Social Theory (2017). Hip Hop Feminism. https://globalsocialtheory.org/topics/hip-hop-feminism/

Rose, Tricia (1994) Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press.

Ogbar, Jeffrey O.G. (2007). Hip Hop Revolution: The Culture and Poltiics of Rap. Chapters One-Two (pp. 9-72).