Breaking Through the Glass Ceiling: A Closer Look at Sexism and the Gender Wage Gap

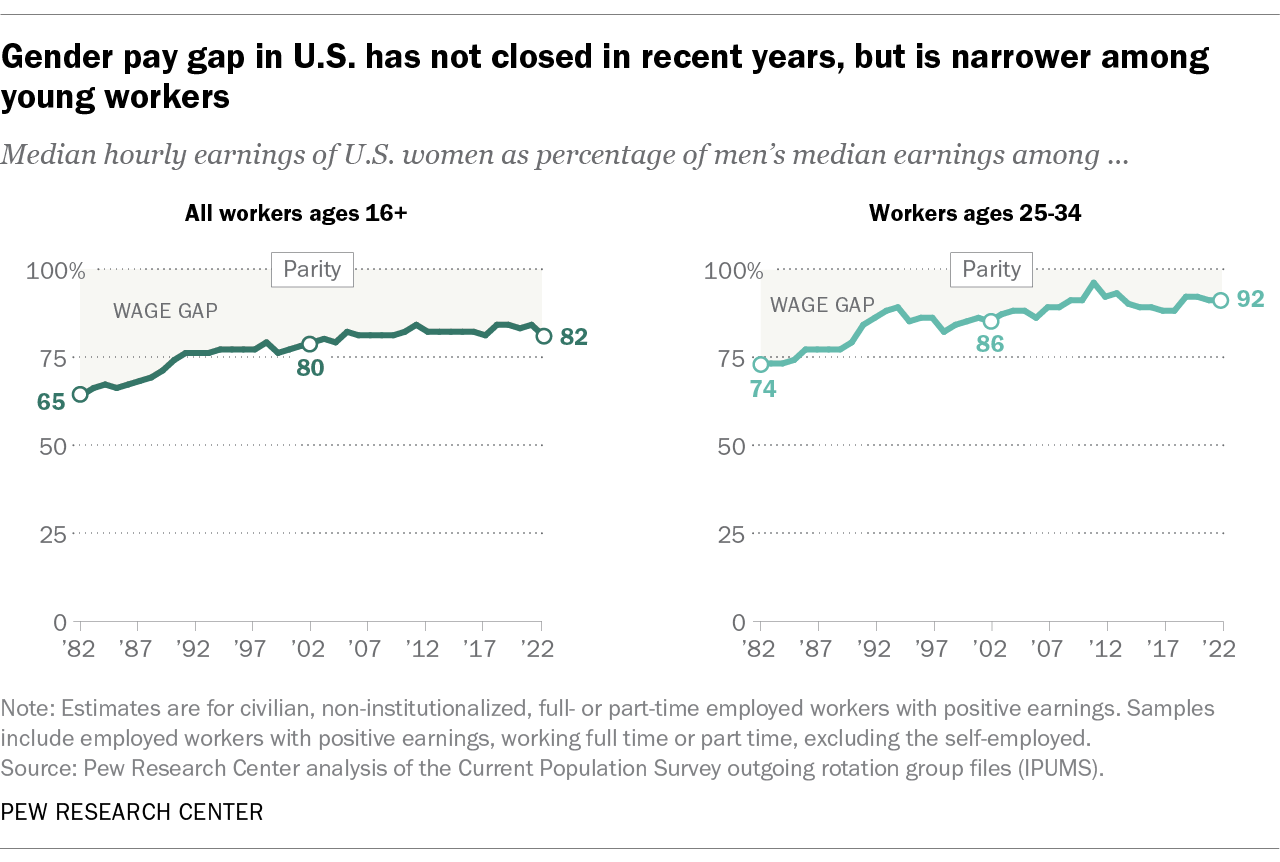

The gender gap in pay has remained relatively stable in the United States over the past 20 years or so. In 2022, women earned an average of 82% of what men earned, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. These results are similar to where the pay gap stood in 2002, when women earned 80% as much as men.

Sexism has been a persistent dark cloud hanging over workplaces, institutions, and society. From subtle biases to overt discrimination, men and women are not equal in the workplace despite decades of progress. Even though women have made strides, challenging invisible barriers—”glass ceiling”—we continue to impede the upward mobility of women in almost every profession. At the heart of this lies the gender wage gap, a tangible reminder of how entrenched ideas about gender are and how they still influence the entire hierarchy of the working world.

Lisa Wade and Myra Marx Ferree’s Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions offers a profound exploration of how gender operates within society—shaping opportunities, dictating norms, and perpetuating inequity. In their book, Wade and Ferree examine gender not as a fixed trait but as a social construct, reinforced by institutions and interactions that perpetuate power imbalances. Gender is performative on many levels, and we uphold that system knowing it privileges men and sidelines women. No matter how you spin n it, gender is a social construction; one that is shaped by the very institutions we trust.

We have to start examining how institutional structures reinforce and perpetuate gendered roles. Gender, like so many social constructions, are learned and institutionalized through daily interactions and social expectations.

That’s polarized in the entire notion of the metaphorical glass ceiling. This term often elicits the belief that there is an invisible barrier—a transparent wall that prevents women from advancing in their careers, despite their qualifications or experience. It isn’t just a barrier; it’s a product of deep-rooted sexism in both corporate structures and cultural attitudes. Women, particularly BIPOC women, are frequently seen as less capable of leadership roles, even if they’ve demonstrate the necessary skills. That’s the problem. There is a social conditioning that has plagued most of us and that is the idea that somehow women are inferior to men (I call bullshit). Even though we had hopes that policies relating to gender equality had evolved, the glass ceiling is a stark reminder that we’ve still got a long way to go.

Despite the gains in gender equality, the wage gap not only intersects, but dominates the work culture. Women, on average, continue to earn less than men for doing the same work. In fact, research consistently shows that women are paid approximately $0.84 cents for every dollar earned by men in comparable roles, with women of color facing even greater disparities. This isn’t due to a lack of effort, talent, or ambition on the part of women, but it is an undeniable result of deeply ingrained biases that undervalue a woman’s work. Traditional roles, even in highly skilled professions, are often perceived as less important, less demanding, or less worthy of high compensation. That triples if you’re a mom, or dare get pregnant while climbing the corporate ladder.

The workplace is a prime example of how these forces operate. When a woman is passed over for a promotion in favor of a male colleague, it’s not just an individual choice—it reflects broader societal norms that position men as the primary earners and decision-makers. When women are underpaid, it’s not because they lack the same qualifications as their male counterparts, but because the institution has been built to undervalue their labor.

The glass ceiling and the wage gap are not simply byproducts of personal decisions, but systemic issues embedded in the structures that govern our lives.

[A glass ceiling is a metaphor first used by feminists in reference to barriers in the careers of high-achieving women. It was coined by Marilyn Loden during a speech in 1978.]A glass ceiling is a metaphor usually applied to women, used to represent an invisible barrier that prevents a given demographic from rising beyond a certain level in a hierarchy.

PEW RESEARCH (2023)

The wage gap is a reflection of societal values that place women in subordinate roles. The consequences are far-reaching. When women are paid less, they have less financial independence, which affects their ability to invest in their futures, access quality healthcare, or secure retirement. The road to equality is not an easy one, but it is one we have to be devoted to walking. It requires not only acknowledging the barriers but actively dismantling them. I hope all companies adopt policies that promote equal pay, offer transparent career advancement opportunities, and foster inclusive environments where women, especially those from marginalized communities, are not just welcomed but empowered. I also hope we challenge the cultural narratives around gender that place limitations on what women can achieve.

Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions offers us a lens through which we can better understand how deeply embedded these structures are, but it also reminds us that change is possible. It’s a call to action for both individuals and institutions to examine how gender influences their actions and to consider how they might contribute to putting an end to sexism. As we move forward, let’s remember that equality is not a gift but a right—and one that is long overdue.

Let’s break through that fucking glass …

The term “glass ceiling” refers to the sometimes-invisible barrier to success that many women come up against in their careers. Management consultant Marilyn Loden coined the phrase almost 40 years ago but says it is still as relevant as ever.

I first used the phrase “glass ceiling” in 1978 during a panel discussion about women’s aspirations. As I listened, I noted how the (female) panellists focused on the deficiencies in women’s socialisation, the self-deprecating ways in which women behaved, and the poor self-image that many women allegedly carried. It was a struggle to sit quietly and listen to the criticisms.

True, women did seem unable to climb the career ladder beyond the lowest rung of middle management, but I argued that the “invisible glass ceiling” – the barriers to advancement that were cultural not personal – was doing the bulk of the damage to women’s career aspirations and opportunities. I was an experienced HR professional in the telecoms industry, and yet was often told by my male boss to “smile more”. He made a point of commenting on my appearance at literally every meeting.

On the occasions when there was more than one woman manager at a meeting, there were usually comments made if the two sat together. On several occasions, I was told that the advancement of women within middle management was “degrading the importance” of these positions. Once I was told that despite my better performance record, a promotion I was hoping for was going to a male peer. The reason given was that he was a “family man” – that he was the main breadwinner and so needed the money more.”

During the 1970s and into the 1980s, there were no laws in place in the US to protect women from workplace harassment or assault. There was also no awareness in organisations about the severity of the problem and zero interest in hearing about or resolving it.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. For our 2017 season we challenged them to tackle four of the biggest problems facing women today – the glass ceiling, female illiteracy, harassment in public spaces and sexism in sport. #100Women

Rather than accept the glass ceiling as inevitable, it is time for institutions to acknowledge that the embedded biases in their cultures predisposing many men for career success while diminishing the strengths, styles and capabilities of the majority of talented women must be eradicated.